Asian capital market integration: theory and evidence

| Corporate finance | |

|---|---|

| |

| Authors | |

| Cyn-Young Park | Asian Development Bank |

The following is an extract from a longer paper that also investigates capital market integration in emerging Asia. The publication can be downloaded in full here

Introduction

As articulated by Cavoli, Rajan, and Siregar (2004) in their survey of East Asian financial integration, financial integration is a multidimensional process closely associated with development of financial markets. It is thus unsurprising that the deregulation of the financial sector in Asia that began during the 1980s and resulted in a significant increase in cross-border financial transactions ultimately led to the region’s ongoing financial integration.

During the period following the Asian financial crisis of 1997, many Asian economies modernised their financial sectors and strengthened linkages with the financial sectors of other economies in the region. This has led to considerable maturation of many of the region’s domestic capital markets, its local-currency bond markets in particular. The soundness of the region’s domestic banking systems has likewise improved, in that domestic capacity for financial supervision has become more sophisticated. Intra-regional financial sector policy coordination has likewise strengthened, as demonstrated by the ongoing development of regional arrangements for macroeconomic monitoring and liquidity support. Nevertheless, there remains significant variation in the degree to which the region’s domestic capital markets have matured and integrated with others in the region and beyond.

Economic theory suggests that financial integration brings with it significant benefits, including lower costs of trading financial assets, more diverse investor portfolios, and more stable consumption patterns, particularly during periods when the level of economic activity fluctuates widely. Given the absence of restrictions on capital mobility, financial integration allows the level of domestic investment to no longer be constrained by the size of the domestic savings pool, since integration allows foreign capital to be used to underwrite domestic investment. This appears to be an important feature of financial integration, given the direct, positive relationship between domestic savings and investment confirmed by publication of Feldstein and Horioka’s seminal paper in 1980, as well as similar literature that followed in its wake. While more recent studies report a weakening in this relationship in advanced economies due to international financial integration, the Feldstein–Horioka puzzle of why investment remains linked to domestic savings remains unresolved, the conventional wisdom of financial globalisation that has developed over the past few decades notwithstanding.

Economic theory suggests that absence of restrictions on capital mobility increases the degree of efficiency with which international financial resources are allocated. The rationale for this view is that capital should automatically flow from capital-abundant to capital-scarce countries, the returns to capital being higher in the latter set of countries than in the former. In turn, the rationale holds that capital flows of this nature supplement the domestic savings pool in capital-scarce countries, thereby allowing domestic investment in such countries to increase and economic growth to accelerate. However, the empirical evidence concerning this matter suggests quite the opposite. It in fact confirms that Asia’s considerable net savings tend to flow to capital-abundant countries rather than to capital-scarce ones as the theory would predict. In the wake of Lucas’ now-famous 1990 paper, this disparity between what economic theory would predict and what actually occurs is often referred to as the “Lucas Paradox” or the “Lucas Puzzle.”

Many economists – including Lucas himself – have offered explanations as to why capital fails to flow from capital-abundant to capital-scarce countries. These explanations fall into two broad groups (Alfaro, Kalemli-Ozcan, and Volosovych 2005), the first of which focuses on differences in fundamental economic variables. Examples of the latter include the degree of technological development, presence or absence of particular critical factors of production, or differences in the level of the output–capital price ratio, government policies, or institutional quality. Ultimately, this set of explanations attempts to provide a rationale for the real-world fact that some countries attract more foreign investment than others. The second group of explanations focuses on capital market imperfections, and the differing stage of development of financial markets in advanced and emerging economies (Martin and Taddei 2012, and Matsuyama 2007). The theoretical foundation for this group of explanations is that capital flows respond to the risk-adjusted rate of return to capital rather than to its corresponding nominal rate. Thus, the higher level of risk associated with the nominal expected returns to capital in capital-scarce countries prevents real-world flows from corresponding to those predicted by the theory. In other words, once adjusted for risk, the difference in the rate of return to capital in capital-scarce countries as compared to capital-abundant countries is simply insufficient to cause capital to flow in the direction suggested by economic theory. Further, because of the sheer volume and quality of information transmitted by credit markets in advanced countries, more capital flows into such economies than would otherwise be the case.

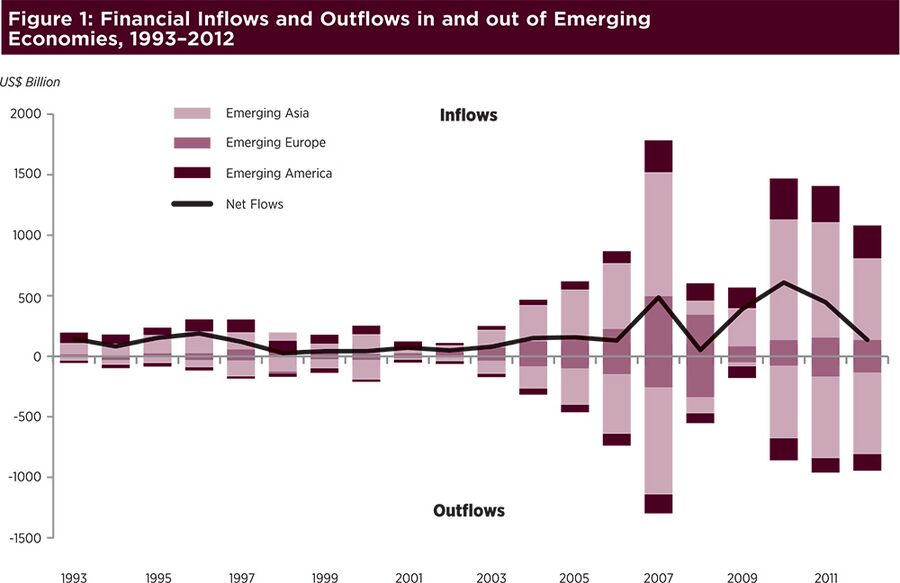

To sum up thus far, while the volume of cross-border capital flows has increased substantially since the mid-1990s (Figure 1), the paradox that articulates the inconsistency between the direction of capital flows predicted by the theory and what actually occurs remains largely unresolved. Indeed, Gourinchas and Jeanne (2007) find a natural tendency for capital to flow toward countries that invest and grow less than other countries. This phenomenon was dubbed the “allocation puzzle” by Prasad et al. (2007), as it flies in the face of the neoclassical view that differences in productivity growth determine the international allocation of capital.

Prasad, Rajan, and Subramanian (2007) also find that developing countries that invest more and rely less on foreign capital grow faster than countries that invest more, but rely more on foreign capital as a funding source for financing such investment. They suggest that even in faster-growing developing countries, the capacity for absorbing foreign capital may still be limited, either because of underdeveloped financial markets, or because of a natural tendency toward overvaluation of domestic currency resulting from rapid capital inflows.

Ultimately, the recurring episodes of financial turmoil that have occurred over the past two decades illustrate that increasingly integrated financial markets have a tendency to experience financial crises, and that the negative impacts of such crises tend to spill over into the markets in which financial assets are traded. In this regard, there is little doubt that abrupt swings in global investor sentiment have impacted the performance of Asia’s domestic equity markets over previous decades. For example, during the global financial crisis of 2008–2009, emerging Asia’s equity markets experienced sharp reversals in foreign portfolio investment inflows as a result of deleveraging of global financial institutions, as well as a sharp increase in investor risk aversion, this being particularly true of markets in which foreign investor participation had been relatively high.

Such outcomes suggest that the benefits of financial integration predicted by economic theory have somehow not been fully achieved. There are a number of reasons why this may be so. For example, financial integration at the global level is incomplete. This may be one reason why the actual pattern of international capital flows diverges considerably from that predicted by theory as noted above. Further, financial integration often brings with it increased risk in the form of volatility of asset prices and then financial market returns, as well as abrupt reversals in capital flows. Such outcomes – which are familiar to many emerging market economies – underscore the importance of appropriate financial supervision when moving the domestic economy toward greater overall financial openness, and loosening of restrictions on capital accounts in particular.

In this regard, it is important for policymakers to understand that there are varying degrees of financial integration, each of which has implications for stability of the domestic financial system, as well as the ability of the domestic economy to absorb shocks such as increased volatility in financial market returns or reversals in international capital flows. Finally, particularly in cases in which financial integration is pursued in a deliberate and methodical manner – such as in emerging Asia – the progress achieved tends to be far from uniform across individual economies, as well as across the various subsectors that comprise the overall domestic financial sector.

This study has two major objectives. First, it reviews the progress emerging Asia has achieved thus far in capital market integration. Second, it assesses the degree to which the financial integration that has been achieved has increased the vulnerability of the region’s individual economies to the negative impacts of financial crises generated elsewhere in the region or at the global level. The overall goal of such analysis is to better understand how the costs to the domestic economy associated with financial integration may be minimised, so as to maximise the net benefits potentially available from financial integration. From a policy-making perspective, a key issue confronting regional financial cooperation and integration is how best to shape national and regional policies in a way that allows the region’s individual economies to maximise the potential gains from financial integration, while at the same time minimising exposure to the risks associated with it.

The full paper is organised as follows. Section II assesses the degree to which de facto as opposed to de jure financial integration has been achieved in emerging Asia. In this regard, Section II uses several widely accepted quantitative indicators to highlight recent developments in financial integration at the regional and subregional levels. Section III then quantitatively estimates the degree to which actual integration has been achieved in equity and bond markets in emerging Asia. Section IV uses principal component analysis to assess the extent to which financial crises generated at the regional and global levels have impacted the financial markets of individual economies in emerging Asia. The conclusions and policy recommendations presented in Section V then complete the paper.

De facto vs. de jure financial integration

While there is no universally accepted definition or singular quantitative measure of financial integration, most observers agree that it is closely associated with financial openness and capital mobility. Figure 1 depicts gross and net financial flows in and out of emerging market economies in Asia, Europe, and Latin America. Mirroring the global trend in financial and capital account deregulation that occurred during the 1980s and 1990s, capital flows into emerging market economies surged and then peaked just prior to the global financial crisis of 2008.1 Asia has become a major destination for such capital flows, accounting for nearly 60% of total financial flows into emerging market economies during the period prior to the global financial crisis.

Note: Emerging Asia includes People's Republic of China; Hong Kong, China; India; Indonesia; Republic of Korea; Malaysia; Philippines; Singapore; Taipei, China; Thailand; and Vietnam. Emerging Europe includes Belarus; Bulgaria; Czech Republic; Estonia; Hungary; Latvia; Lithuania; Moldova; Poland; Romania; Russian Federation; Slovak Republic; and Ukraine. Emerging Latin America includes Argentina; Brazil; Chile; Colombia; Dominican Republic; Ecuador; Guatemala; Mexico; Peru; and Venezuela. Emerging Markets includes countries in Emerging Asia, Europe and Latin America. Data on inflows are liabilities; while outflows are assets. Foreign direct inflows from 1990-2004 refer to direct investments in the reporting country. Other investments include financial derivatives. Data from 2005 onwards follow Balance of Payments Manual 6 (BPM6).

Source: Author's calculations using data from International Financial Statistics, International Monetary Fund; and national sources.

There are several ways to quantitatively assess financial openness, and thence financial integration. The first of these would be to count the number of legal restrictions on cross-border capital flows applicable to the economy concerned. This would constitute a de jure measure of financial integration, since it is based on legal restrictions currently in force. A wide variety of such restrictions are currently in use, including price- and quantity-based controls on the international movement of capital, as well as restrictions on equity holdings by nonresidents. Indeed, the International Monetary Fund reports more than 60 different types of such controls in its Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions (AREAER). The inherent weakness of this approach is that counting capital controls gives us no information whatsoever regarding the degree to which such restrictions are effective in limiting the extent of international capital flows.

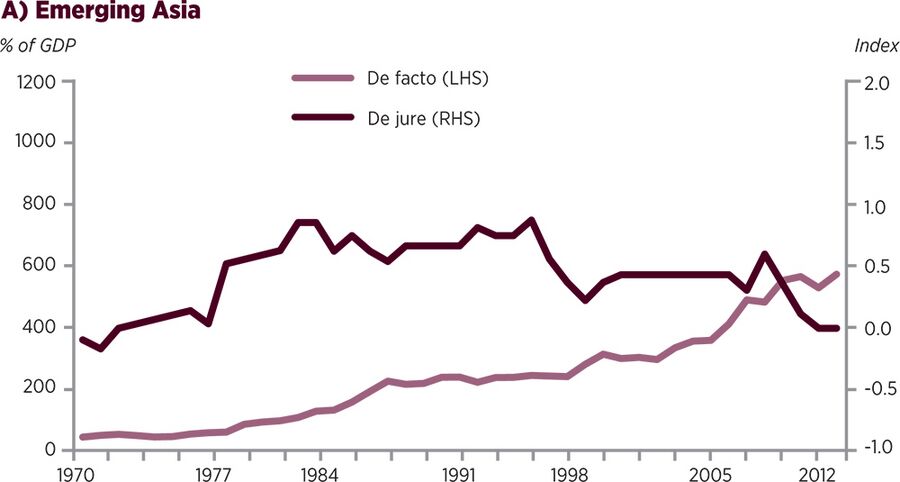

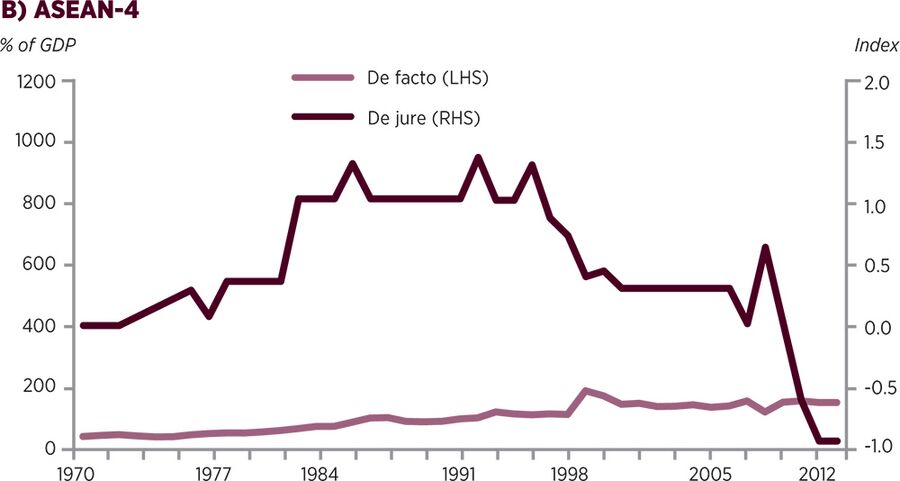

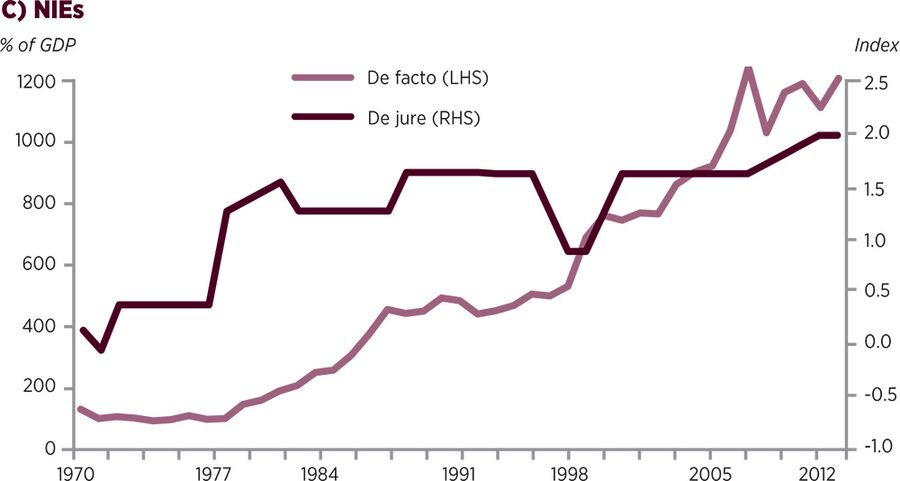

A second approach would be to use an actual measure of financial openness, such as assessing actual cross-border capital flows, since the latter directly reflect the degree of financial openness of the economy concerned. In many ways, such an approach constitutes an improvement over the legal approach, in that, what matters is not how open capital markets appear on paper, but how integrated they are in practice. However, such a measure raises the question as to whether gross or net financial flows constitute the more suitable measure, particularly since both tend to be volatile and often subject to procedural issues in their measurement. Because of such shortcomings, the stock of foreign assets and liabilities (IMF 2009) is often used as an additional measure of actual financial openness and then financial integration. Figures 2a–c depict de jure and de facto financial integration indexes for emerging Asia and its various subgroupings. The measure of legal financial integration used is the index initially developed by Chinn and Ito (2006) to measure capital account openness, which assesses the existence of legal restrictions on cross-border financial transactions as reported in the AREAER, values of greater magnitude indicating a greater degree of financial openness.

Conversely, the summed gross stock of foreign assets and liabilities as a percentage of gross domestic product is the actual measure of financial integration depicted in Figure 2a–c. The values depicted in Figure 2 were calculated from an update of the dataset constructed by Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (2007), and were extended with data from the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) International Investment Position Database.

As depicted in Figures 2a–c, emerging Asia’s legal financial integration index rose sharply during the late 1970s and early 1980s, reflecting the wave of financial deregulation that occurred across the region during this period. Although there were some adjustments to legal restrictions relating to financial integration in the wake of this “big bang” style of financial deregulation that occurred during the 1970s and 1980s, the legal financial integration index remained high up until the late-1990s, the period just prior to the Asian financial crisis. The fall in the legal financial integration index around the time of the Asian financial crisis reflects increased foreign exchange interventions by Asian economies in the run-up to the crisis of 1997, as well as the introduction of capital control measures following the outbreak of the crisis.

Notably, the trends in the legal financial integration indexes for the newly industrialising economies (NIEs) and the ASEAN-4 countries diverge quite widely in the wake of the crisis of 1997.2 In particular, while the NIEs quickly dismantled the temporary capital control measures put into place in the wake of the crisis and continued on their medium-term path of financial deregulation, the ASEAN-4 countries sustained their post-Asian financial crisis controls overall, and even introduced additional controls during the global financial crisis of 2008.

Interestingly, the actual financial integration indexes for all three sets of countries – emerging Asia overall, the ASEAN-4, and the NIEs – show a steady uptrend despite the declines that occurred in the legal financial integration index in the ASEAN-4. This highlights the substantial gap between de facto and de jure measures of financial openness and integration. In short, the fact that numerous developing countries impose significant legal controls on the international movement of capital does not mean that such controls are particularly effective in curbing international capital flows. Actual financial integration – as measured by capital flows and cross-border financial asset holdings – may significantly exceed the level implied by corresponding legal controls. This seems particularly relevant to the ASEAN-4 countries, where de facto financial integration measure increased rather sharply during the period following the 1997 crisis, just when the de jure measure of financial integration fell significantly.

Park and Lee (2011) report that capital flows in and out of emerging Asia have consistently increased, and that over the past decade these have been particularly driven by portfolio investment flows. Their study likewise analysed international portfolio asset holdings using the IMF’s Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey (CPIS), which disaggregates each economy’s stock of portfolio investment assets by country of residence of the issuer of the asset concerned3. Park and Lee find a sharp increase in emerging Asia’s international portfolio asset holdings over the study period, implying a significant increase in the degree of financial openness and integration achieved by the region overall. However, when disaggregated by subregional grouping as well as asset classification, their assessment of the region’s foreign asset holdings suggests that the degree of financial integration achieved by the region’s various subgroupings of economies and market segments is far from uniform.

Such findings suggest that there remains considerable room for improvement in regional financial integration in two ways. First, although emerging Asia’s foreign portfolio assets are increasingly held within the region, advanced economies still account for a major share of its foreign portfolio assets. Second, there is a considerable difference in the degree of financial market development and integration as regards the equity and bond markets. In particular, Park and Lee find that the region’s equity markets are relatively more open and integrated as compared to its domestic currency bond markets. Emerging Asia’s foreign asset holdings are also skewed toward equities as opposed to debt securities. Further, the region’s domestic currency bond markets remain largely segmented, their limited integration probably reflecting a correspondingly limited level of development of this segment of the financial market.

1In this paper, the phrase “emerging market economies” refers to the emerging economies of Asia, Europe, and Latin America. Similarly, “emerging Asia” refers the People’s Republic of China (PRC); Hong Kong, China; India; Indonesia; the Republic of Korea; Malaysia, the Philippines; Singapore; Taipei, China; Thailand; and Vietnam. “Emerging Europe” thus refers to Belarus, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Poland, Romania, the Russian Federation, the Slovak Republic, and the Ukraine, and “emerging Latin America” refers to Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Columbia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, Peru, and Venezuela.

2As used in this chapter, the phrase “newly industrialising economies” (NIEs) refers to Hong Kong, China; the Republic of Korea; Singapore, and Taipei, China. Similarly, the phrase “ASEAN-4” refers to Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand, these countries being four of the ten members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). At this writing, ASEAN’s full membership includes Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Malaysia, Myanmar (Burma), the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.

3The first Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey (CPIS) dataset which was published in 1998 reflected data for 1997. However, annual CPIS data only became available in 2001.

Note: The de facto (LHS = left hand scale) measure that appears in Figures 2a-c refers to the sum of foreign assets and liabilities expressed as a percentage of GDP. This measure is taken from the Lane and Milesi-Ferreti External Wealth of Nations dataset, and was extended using data from the International Monetary Fund's (IMF's) International Investment Position (IIP). The de jure (RHS = right hand scale) measure refers to the estimated Chinn-Ito Index, which is based on the IMF's Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions. The Emerging Asia grouping includes the People's Republic of China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand. The Newly Industrialising Economies (NIEs) grouping includes Hong Kong, China; the Republic of Korea; Singapore; and Taipei, China. Source: External Wealth of Nations Dataset and the Chinn-Ito Index.