Corporate credit ratings: a quick guide

| Corporate finance | |

|---|---|

| |

| Author | |

| Lucy Symondson | Tel: +44 (0)20 7280 5725 |

What is a credit rating?

In its simplest form, a credit rating is a formal, independent opinion of a borrower’s ability to service its debt obligations (i.e. that interest and principal will be repaid in full and on time). The majority of ratings are publicly disclosed (though not always, as we will come on to later) and are provided for the benefit of debt investors in their investment appraisal process (where the rating is applied to a specific debt instrument), although they are also used by creditors and other parties for understanding a group’s or an entity’s credit profile (where a Corporate Family rating or an Issuer credit rating may be assigned). Despite this, the cost for obtaining a credit rating is borne by the company or issuer.

From a borrower’s perspective, a credit rating is generally a requirement of public bond issuance (some issuers are able to issue unrated bonds e.g. Christian Dior; however, this tends to be relatively infrequent) and certain loan structures (particularly those which are distributed to institutional lenders, such as CLO funds) and thus provides access to a wider range of lenders and debt products. The European debt markets have seen a significant shift in recent years as European corporates have sought to rebalance their funding sources away from traditional bank financing and towards bond finance. As a result, the importance of achieving a strong credit rating is relevant for a wider audience than ever before.

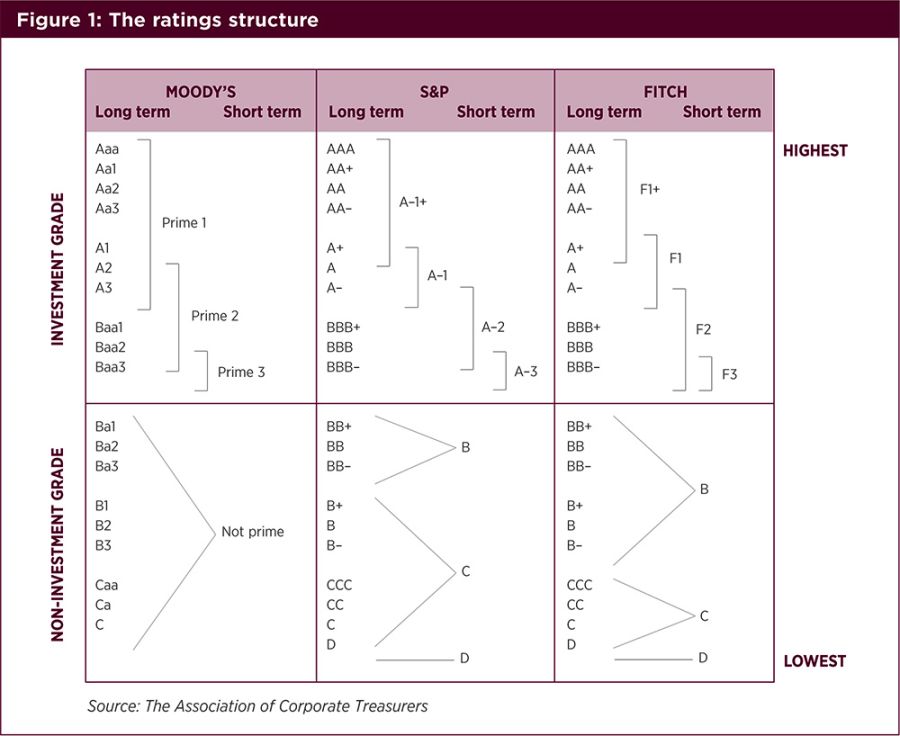

The rating agencies distinguish between rating short-term (<365 days) and long-term (1+ year) obligations, owing to the different investment dynamics of the different investor bases. In general, there is little value in having a short-term rating unless issuing commercial paper and such rating is in the top two categories, as it is only really used in the (short-term) commercial paper market, which requires minimum P2/A-1/F1 ratings. Investors, creditors and other interested parties tend to look to a borrower’s long-term credit rating as a general measure of creditworthiness.

An alternative category of credit references are those provided by Dunn & Bradstreet, Experian and others. In addition to being used by trade creditors and other supply chain counterparties, D&B scores are used in calculating the UK pension regulator’s PPF levy. However, such scores tend not to be used by debt investors to examine debt instruments and so are not considered further in this guide.

The rating agencies and the types of credit rating

Credit ratings are predominantly provided by three main independent rating agencies, namely Moody’s Investors Service (Moody’s), Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services (S&P) and Fitch Ratings (Fitch), although there are others such as Dominion Bond Rating Service (DBRS). Ratings themselves can be provided to cover individual issuers, such as corporations or sovereign governments, or specific, individual debt instruments and encompass both long-term ratings and short-term ratings.

Although the agencies adopt different rating scales, there is equivalence across the scales, which facilitates comparison between ratings provided by each rating agency. For example a Baa1 rating provided from Moody’s is equivalent to a BBB+ rating from S&P and BBB+ from Fitch. The full rating scales for each rating agency are shown in more detail in Figure 1.

Ratings are typically separated into one of two broad classifications: 1) “Investment Grade”, comprising all ratings from AAA at the top, down to Baa3/BBB-/BBB- at the bottom; and 2) “Non-Investment Grade” (aka speculative grade, junk, high yield, etc.), comprising all ratings from Ba1/BB+/BB+ through to D (where default has occurred). An investment grade rating is important for certain borrowers to ensure full market access (as some investors face limits on the proportion of sub-investment grade debt they are allowed to hold in a portfolio), achieving flexible documentation and attractive terms on debt issues, and in some cases for the prestige value in front of competitors, customers and suppliers. Sub-investment grade debt issues often require a greater degree of operating and financial restrictions and inevitably attract higher pricing commensurate with a higher level of credit default risk.

The degree of market access is a key benefit of investment grade borrowers. In times of financial turmoil, primary debt markets have historically shown themselves to be relatively volatile with investor funds flowing into and out of the bond markets at short notice. Over the past 4 to 5 years this volatility has manifested itself with the debt capital markets ‘closing’ during periods of uncertainty, often triggered by macro-economic shocks such as the banking crisis across Western Europe and later the Eurozone crisis. When market sentiment subsequently improves, investors invariably look most favourably upon the highest rated issuers which typically reopen the debt markets and provide windows of opportunities for companies to tap often short-lived investor confidence.

An important extension to the concept of a borrower’s or an issue’s credit rating is the rating outlook (positive, stable, negative or Credit Watch developing), which is a function of the ongoing surveillance provided by a rating agency on an issuer or issue and provides a directional evaluation of where the rating is likely to move over time. In addition, certain entities or issues subject to announced or expected major corporate events (typically around M&A) can be placed on credit-watch pending outcome of the event, and in some circumstances the agency will give a view about what would happen to the rating under different outcomes.

Rating agency methodology

Each of the main agencies provide an overview of their detailed rating methodologies on their websites, however, in terms of a broad fundamental approach they all examine a combination of financial risk and business risk in arriving at a credit opinion. The interplay between business risk and financial risk is an important consideration in the rating process. The degree of financial risk which a company is able to tolerate at a specific level of credit quality is heavily influenced by its business risk profile and the dynamics of the industry in which it operates. A company operating in an industry typified by low levels of relative business risk (i.e. those which demonstrate low levels of cyclicality/volatility, or which are supported by high degrees of governmental regulation) may be able to tolerate a higher degree of financial risk than an equivalent company which operates in a more risky business environment at an equivalent level of credit quality. Put another way, two companies with identical financial risk profiles will be rated differently, according to each company’s business risk profile and industry prospects. Understanding these dynamics can be an important advantage for companies looking to go through a credit rating or debt issuance process. In terms of how these two risk categories are typically examined:

- Business risk: Evaluation of strengths/weaknesses of the operations of the entity, including: market position, geographic diversification, sector strengths or weaknesses, market cyclicality, and competitive dynamics. This approach allows businesses to be compared and relative strengths/weaknesses to be identified. As highlighted previously, business risk can be significantly impacted by the nature of the industry in which a company operates.

- Financial risk: Evaluation of the financial flexibility of the entity, including: total sales and profitability measures, margins, growth expectations, liquidity, funding diversity and financial forecasts. At the heart of this analysis is credit ratio analysis, which is used to quantitatively position companies of similar business risk against each other. The level of financial risk tolerance that companies can sustain at a particular rating grade will be significantly impacted by its financial risk profile.

Financial risk analysis

Whilst the examination of business risk can vary from case to case and is often very specific to the particular company and industry under examination, the examination of financial risk tends to be more standardised across different industry sectors. The area of Financial Risk analysis is often distilled (especially for a well known company in a widely rated sector) down to the analysis of a certain number of key credit ratios. Typically this might include the following elements:

- Liquidity – short-term ability to service debt obligations and in particular, measures of cash flow adequacy (typically this is the single most important consideration for rating analysis).

- Long-term capital structure and asset cover measures.

- Accounting and financial policies.

Typical adjustments

Although there are numerous adjustments that can be made to a company’s financial statements as part of a credit rating process, there are a handful of main adjustment rules when it comes to credit ratio analysis. The purpose of these adjustments is to help ensure that key ratios or metrics are presented on a consistent basis across companies which may have differing approaches with respect to certain asset or liability items which in turn can have a significant impact on some of the key metrics examined as part of the credit rating process:

- Pension adjustments: The purpose of this adjustment is to ensure that the full economic obligations with respect to a company’s defined benefit pension scheme are captured on its balance sheet. The full set of adjustments are relatively complex, but the core element involves classifying any defined pension deficit as a liability or debt-like item when calculating Adjusted Net / Total Debt.

- Operating leases: The purpose of this adjustment is to eliminate often notional differences between companies which choose to account for potentially similar assets in very different ways. Specifically, companies may either purchase key assets (through a finance lease or similar) and depreciate them on-balance sheet, or alternatively may instead choose to account for similar assets using operating leases, with no direct balance sheet impact. The analytical approach of the rating agencies is to capitalise operating leases, to bring them on-balance sheet by adjusting reported debt and assets by the present value of lease commitments (with a number of follow-on adjustments to the P&L and calculation of EBITDA).

- Hybrid bonds: Given the different nature of hybrid capital, partial or full equity treatment is typically applied to certain qualifying debt instruments by the rating agencies, with levels (25%/50%/75%/100%) depending on level of subordination, maturity, replacement language and coupon deferral. Borrowers issue hybrids (straight or convertible) to support (or even reach) a desired credit rating or credit profile, reducing (or even eliminating) the need for equity.

Although the above can get you much of the way towards replicating the published credit ratios, it is often difficult to replicate the analysis exactly without explicit guidance from the rating agencies. Each of the main agencies provide publicly available guidance on the typical approach to rating certain sectors, as well as the standard adjustments utilised with respect to off-balance sheet liabilities and other standardised adjustments. However, a clear, transparent relationship with a rating agency is key to ensure that treasurers have a strong understanding of the approach being taken and the potential outcome.

Dealing with the rating agencies

Responsibility for dealing with the rating agencies will usually lie with the corporate treasurer (or occasionally the finance director).

In order to deal effectively with the rating agencies, it is important to understand clearly both how the rating is determined, and also its positioning relative to its peers. An open and regular dialogue with the agencies, together with a clear understanding of the financial adjustments they employ to arrive at the credit ratios, will therefore greatly facilitate a company’s understanding of its own rating headroom, risks and mitigants.

A treasurer with a good grasp of how the rating agencies analyse both the business risk and financial risk of his or her company will be better positioned to understand the likely reaction of the agencies to changes in operating performance (market weakness, increased competition) or corporate events (acquisitions, divestitures and dividends). One particular area to focus on is credit ratio analysis, as an accurate replication of the precise adjustments the agencies use will make the quantitative aspect of the analysis as transparent as possible. When combined with guidance on ratio expectations, the ability to accurately replicate the rating agency adjustments will give the treasurer a useful tool to anticipate the agencies’ likely reaction to various scenarios (such as determining the maximum special dividend that can be made without jeopardising a certain rating).

Understanding the approach that rating agencies adopt is of critical importance to ensure that a company is positioned in the best possible light with respect to its potential credit rating. It is helpful when dealing with the agencies to present in a manner that is immediately comparable with their own analysis, while the provision of consistent reliable information – and the development of a professional relationship with analysts – will significantly support credibility of projections, forecasts and corporate actions.

Information requirements

Although the agencies can have access to a company’s own financial forecasts and other non-public information, what they publish tends to be restricted to historical (public) information only, although there can be statements of expectations or assumptions such as “we expect company X to maintain a ratio of Y in the medium-term”.

The information requirements of the agencies will vary depending on the nature of the corporate and what is available. For larger corporates who already make extensive disclosure, the determination will often be based solely on publicly available information. However, in most cases there will be a higher level of interaction between the company and the agency, and the agency would review both public and non-public information. As a general guide, a corporate should expect to have a transparent relationship with its credit agencies in the same way it would have with a close relationship bank, and consider making available items such as annual budgets, periodic reporting and management meetings.

Alternatives to a public credit rating

As companies find it challenging to raise capital from relationship banks and seek to limit refinancing risk, they are increasingly turning to the debt capital markets (where investor demand is currently strong but ratings are recommended/required) to refinance upcoming maturities. Many unrated companies are therefore considering obtaining a credit rating to ensure smooth capital markets access and as a first step to obtaining a public rating are increasingly using the different services offered by the rating agencies to assess their credit rating. Two of the options companies may consider instead of a public credit rating are:

Rating evaluation/assessment services

Private rating evaluation/assessments services are typically used for internal purposes to help a company better understand what a full rating outcome might be, or what the potential impact of a key financing transaction might be on its credit profile. It is essentially a point-in-time desktop exercise and not a firm Credit Rating, nor is it monitored on an ongoing basis.

The two to three page report typically takes 8 to 10 business days to produce and contains an analysis of public information, but does not include any management meetings and is not sanctioned by a Ratings Committee (and thus is not a formal rating opinion or even a rating indication). It is reviewed by the sector rating analysts for policy consistency, but is little more than a point in time view with no ongoing obligation on either side. This compares with a full (private or public) internal credit rating process which takes four to eight weeks and involves more in-depth analytics, a Management Meeting and a formal Ratings Committee.

Private credit rating

When a company obtains a full corporate credit rating, it can choose to publish the rating or maintain the rating on a private/confidential basis. Both Moody’s and S&P offer a confidential monitored rating service whereby they maintain the confidential credit rating periodically similar to a public rating and the rating can be published on request. Public dissemination of a private credit rating is not permitted.

Other considerations

Public guidance

Guidance provided publicly to debt investors concerning ratings can give support to the rating. For example, publicising your “target rating” will be seen as a moral commitment, and will give investors and agencies comfort that you are committed to a given financial policy. Clearly this undertaking carries its own risks and could impose certain constraints on a company to necessitate hitting a specific rating target.

Credit ratings through the cycle

Although rating agencies claim to “rate through the cycle”, this generally reflects the framework (including ratio targets) and not the potential cyclical recovery prospects of a rated entity. To illustrate the point, over 75% of Moody’s rating changes in 2008 were downgrades compared to 33% in 2007. The high proportion of companies downgraded during a recession is due to the effect of weaker trading on credit metrics and profitability. So although the agencies generally do not revise their methodology or guidance down in a recession (unless sector specific issues are identified), they will actively downgrade companies where target metrics are not maintained.

“What if” rating analysis

When considering a first time rating or a rated issue, or if unsure of the impact of a corporate event (such as an acquisition, disposal or capital return) on an existing rating, it can make sense to take advice from a ratings adviser. Book-runners often offer some form of advisory service as part of the overall issue process but it is important to be comfortable that the incentives of any adviser are closely aligned with those of the company to deliver the best possible rating (to minimise cost of capital and maximise flexibility of financing), rather than delivering terms which might work best from an underwriting perspective. In this respect, an independent rating adviser may be particularly valuable when employed at an early stage in the process, before structure has been determined and banks mandated.

The agencies will offer a desktop credit assessment as a rating guideline (as discussed above). However, if greater certainty of rating outcome is required, the agencies can provide firm rating guidance on a private basis of rating outcome under a particular corporate scenario (e.g. acquisition, disposal, exceptional dividend) under their Rating Evaluation/Assessment Service. The former generally takes two to three weeks and the latter four to eight weeks (but both can be done more quickly in certain situations).

Rating risk

Issuers should be cognisant that it is possible for a rating agency to change its approach or fundamental view of a sector without any change occurring to the credit profile of a company in the “real world”. In November 2013 S&P released its revised corporate methodology. This criteria replaced the 2008 criteria for non financial corporates, with the aim of providing both better clarity on the specific factors used to determine a corporate rating and clear guidance on the weight of each of these factors in the final rating outcome. Associated rating changes represented c.5% of ratings (about 200 issuer credit ratings).

Rating agencies can also change their analytical approach to a specific accounting item. Changes to the assessment of pension deficits in the early 2000s, for example, caused a number of corporates to be downgraded. More recently adjustments to the way hybrid capital is treated serve to remind us that this risk should be borne in mind when planning a capital structure around a rating target. However, as the capital markets become more transparent and investors and issuers more critical, this risk is diminishing.

In the context of capital markets issues, it has become fairly standard for investment grade bond issues to have coupon step-ups which are triggered by ratings downgrades (typically on descent to non-investment grade). For those companies, maintaining investment grade credit ratings is crucial to avoid a steep increase in debt financing costs.

Bank internal credit ratings

Most banks have their own internal risk rating scale and since the implementation of Basel II these broadly map to the rating agency ratings, not least because that is how they have been designed. The bank rating processes, however, tend to be far more numerically mechanical than those of the agencies and consequently their scales may not be directly comparable (also because for example their default definition is different or they capture loss given default differently). Whether publicly rated or not, the agencies influence ratings and cost of debt and a strong understanding of the key credit metrics utilised in the credit rating/appraisal process can be a significant advantage to a corporate treasurer, irrespective of whether they are looking to raise bond or bank finance.

Costs

The costs of obtaining a rating can vary significantly dependent on the type of rating being obtained (full public rating vs. private rating assessment etc.) and the quantum of the debt issue being rated (fees for full public ratings are linked to the quantum of issue). Overall, it is important to have a clear and transparent discussion with the rating agencies to determine which service might best suit the particular requirements of the company and the relative costs associated with each alternative.

Websites

S&P

Moody’s

Fitch